Columbus and the Home Front (World War II) Part 5

- Historic Columbus

- Jul 30, 2025

- 16 min read

The three stories featured in this History Spotlight are from Rebecca Hardaway King, Clason Kyle, and Oscar Stanback.

SOURCES: Columbus and the Home Front: Memories of Columbus, Georgia During World War II. Shaw High School Young Historians, 2007. Images are from the project book, the Columbus Ledger-Enquirer, and the Library of Congress (1940 and 1941).

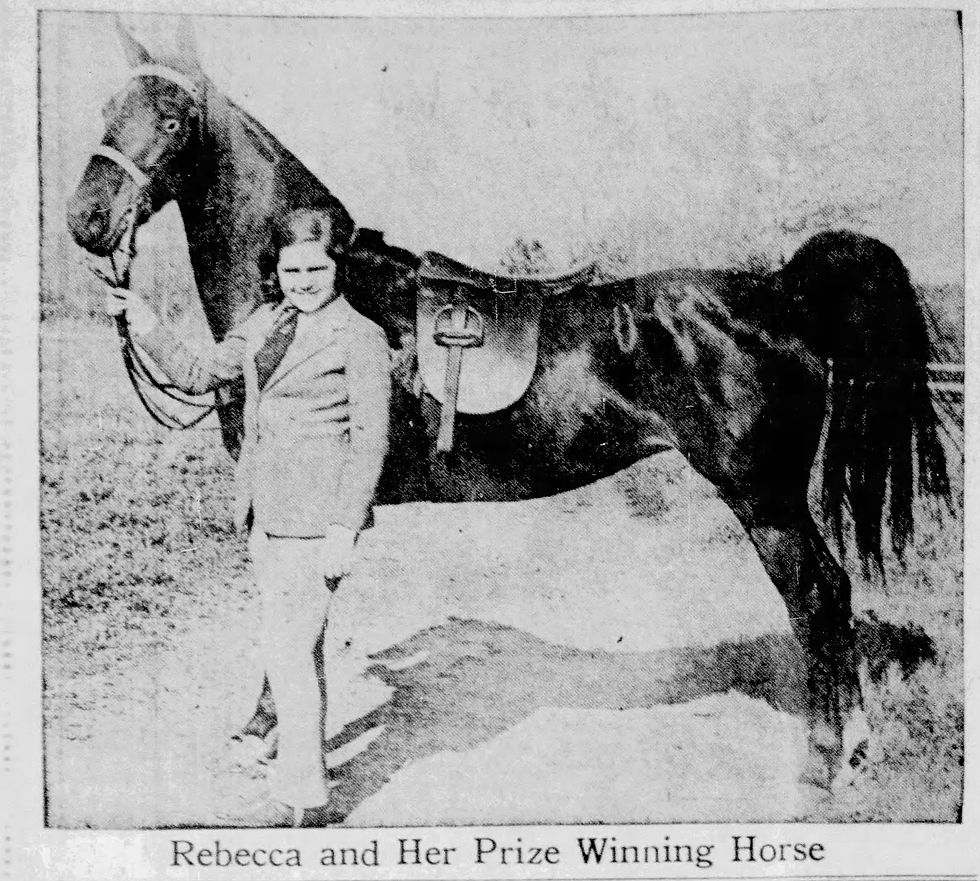

Rebecca Hardaway King – interviewed by Forrest Parker (2006)

Rebecca Hardaway King was born in Columbus on May 27, 1927, the youngest of three children; Ben was her older brother, and Sarah, her older sister, later married Jack Hughston, founder of Hughston Clinic. Her father, Benjamin Hardaway, was the chairman of the Hardaway Construction Company, which had been founded by her grandfather.

In 1941, Mrs. King was 14 years old and a freshman at Columbus High School. Prior to that, she had attended Wynnton Elementary School and 16th Street Elementary. Because her family did not live in the city, when the school at Wynnton had too many students, she and others who lived out in the county were transferred to 16th Street Elementary. After her sophomore year at Columbus, she attended Ogontz, a preparatory school in Philadelphia. Mrs. King admitted she was a precocious child and had many adventures and misadventures during the war years.

She recalls her father returning from a business trip to Puerto Rico before the war, where his company had a construction project. He told his family and friends then that the Japanese were buying huge quantities of scrap metal, and he felt then that war was not far away. When it came, Mrs. King and her friends were playing badminton with friends at the Hardaway house in Midland. They had been to church that Sunday, eaten lunch, and had not been listening to the radio. The news was delivered by friends. "We were in shock," she remembers.

Living out in the country, recreational activities were limited, especially with the restrictions of gas rationing. Mrs. King recalls Morrison's Cafeteria as a popular eating place, along with Spano's Restaurant. Teens enjoyed the Goo Goo Drive-In, across from Linwood Cemetery. Her favorite was the fried steak sandwiches served there. The Empire Café was also a popular eating place, especially late at night after dances. There were two major theaters downtown at the time – The Grand, which later was the site of the Bradley Theater, was the best one, while The Rialto was less preferred – "you didn't go there unless you were really desperate."

She recalls that The Royal Theater, which later became the Three Arts, was also available, showing mostly cowboy movies. Although there was an active social life during that time, she was too young to take part in many of the activities, although she did attend dances occasionally at Ft. Benning. Her favorite singer was Frank Sinatra.

Gas rationing affected people at all levels. Mrs. King remembers an embarrassing incident that happened to her mother. Evidently, cars had to have stickers according to the category of gas rationing they qualified for. Because her own car was short of gas on this particular occasion, her mother used Mr. Hardaway's official business car to attend a club meeting. During the meeting, a policeman cited several cars which were not being used for their intended purposes, and the names of the owners appeared in the paper the next day. Mr. Hardaway was not happy, and "that was the last time that happened, I can tell you!"

At Ogontz, later in the war, Mrs. King remembers that there was a strict dress code for girls going out after school. Despite the rationing of silk/nylon material, which was used for parachutes, girls at the school were required to wear silk stockings. If they didn't wear them, they would be sent back to their rooms. Leg make-up and drawing a line down the back of the leg with an eyebrow pencil to imitate a seam, which worked back in Columbus, was not sufficient.

Mrs. King started drinking coffee while at Ogontz, and because sugar was rationed, she always drank it black, a habit she continues to this day. Tires were rationed as well, and she recalls that the retreads that were sold were the cause of many blowouts. Billboards advertising Lucky Strike cigarettes reported that the characteristic green package used by the company had been changed to white, with the slogan "Lucky Strike green has gone to war" Even after the war, there was a shortage of meat. Mrs. King said that her father was in New York City on business and was eating dinner in the Starlight Room of the Waldorf Astoria. Upon ordering steak, which was on the menu, the waiter reportedly told him, "If you want steak, you should have ridden it up here." "Daddy was furious," she said.

Although Mrs. King did not work at the USO during the war, she did help serve punch at the canteen set up for soldiers at St. Paul's Church at 3rd Avenue and 13th Street. Evidently, there was no dancing allowed, but it was a place where soldiers could come for a drink, eat a snack, and have some conversation with Christian young ladies. Contact with the soldiers was strictly monitored. The woman who was the chaperone was "the meanest old lady in Columbus," according to Mrs. King.

The mention of Phenix City brought a matter-of-fact response from Mrs. King. All sorts of people went to Phenix City—not just soldiers. "Columbus was a quiet place and in Phenix City, there was music, entertainment, and whiskey."

Mrs. King had numerous anecdotes about her life during the war which demonstrate what conditions were like at the time, and the fact that she was forever "getting into trouble." Traveling to Ogontz in Philadelphia involved an overnight train trip with a transfer in Atlanta. Unless one had a private sleeping compartment, which was both expensive and difficult to obtain during the war, overnight travelers used sleeping cars with bunk beds and curtains for privacy— it was not very private.

Returning to Columbus during one school break, Mrs. King related that after conversing with friends in the lounge car, she went back to her seat in the passenger coach only to find that the train had already stopped, disconnected her car, and continued on. Luckily, she was able to get off at the next stop and catch another train back to Atlanta, where another passenger from Columbus was kind enough to provide her with transportation to Columbus.

Returning to Columbus when school was out, Mrs. King did find time occasionally to date some young officers training at Fort Benning. The family had close connections to the military, not only through Mr. Hardaway's business contacts, but also through her uncle, General Manton Eddy, who commanded the 9th Infantry Division in WWII. These connections once led to a date with John Eisenhower, the son of General Dwight Eisenhower. A cadet at the time, John and Rebecca did not hit it off. "He was the most unattractive man I ever met" was her comment.

Another date with a cadet led to her being banned from the Military Academy at West Point. At Ogontz, a blind date had been arranged for her at West Point, where she found out that an acquaintance who was on his way overseas would be passing through. After her date with the cadet, she snuck out of her boarding house to bid farewell to her friend. Returning from Bear Mountain, she was caught and ultimately informed that she was no longer welcome at the Academy.

While still at Columbus High, she and a friend decided to play hooky one day. At the time, the school was ruled with an iron fist by Mr. B. F. Kendrick, feared and respected by all the students. Feigning illness, they departed the school and caught a bus or trolley downtown, where they decided to see a movie at The Rialto Theater. Enjoying the movie up in the balcony, she was startled when the movie was interrupted by the announcement "If Rebecca Hardaway is in the theater, please come to the box office immediately." Thinking she was about to come face to face with Mr. Kendrick, she found to her relief it was her father's chauffeur, who took her home from school in the afternoons. He had gone to pick her up at school and then searched the town for her. This was the last place that he thought she might be. Fearful of being reported to Mr. Kendrick, she tearfully admitted everything to her mother when she got home. She promised her that she had never been so scared in her life and that she would never do something like that again.

Mr. Hardaway owned a yacht, which at the beginning of the war was moored in Miami. All yacht owners were told to remove their boats from the coastal areas. Mr. Hardaway took the girls with him to sail the boat up the intercoastal, through Lake Okeechobee, and then on to Pensacola. Near Fort Lauderdale, sailing at night, Mr. Hardaway had his boat running lights on. A coastal watcher mistook the bobbing lights for an attempt to send a signal to the enemy submarines, and the yacht was stopped, and Mr. Hardaway was required to appear in court to explain his actions. He was able to do so, and the yacht was allowed to continue its journey to Pensacola.

The death of President Roosevelt in April 1945 came when she was at school in Ogontz. Mrs. King had met FDR during one of his trips to Warm Springs. She was surprised at the reaction of some of her classmates at the school, whose families obviously were upper-crust Republicans. They were running around and clapping at the news.

In the summer of 1945, Rebecca Hardaway married Buford King, who was a friend of her brother, Ben. One of five sons whose family owned the King Grocery Company, Lieutenant King had seen action in Africa, Italy, and France. Wounded after the D-Day invasion in action around St. Lo, he received a Silver Star for his action.

925 Blandford Avenue is located in the Wynn's Hill - Overlook Historic District. Built in 1925 for the Kyle family, this home is situated on a large lot with a beautiful pool and pool house arrangement that is highly unique for the neighborhood. New owners Rebekah and Drew Brooks have done a wonderful job on the renovation and will be great stewards of this storied historic home owned by one of Historic Columbus’ founding members, Clason Kyle.

It is currently under renovation on the exterior.

F. Clason Kyle – interviewed by Crystal Nguyen, Kelsey Malkin, and Josh Nichols (2006)

Fleming Clason Kyle was born on May 5, 1929, just months before the Stock Market Crash that signaled the onset of the Great Depression. Despite the troubled economic times, Mr. Kyle enjoyed a happy childhood. As the youngest child, he was surrounded by a loving family that extended to grandparents, aunts, and uncles. His family lived at 925 Blandford Avenue (pictured above). He attended Wynnton Elementary School and enjoyed playing with neighborhood friends. His family's home was joined on one side by a lot, and it was there that Mr. Kyle enjoyed playing softball with his friends. The lot was referred to as "Kyle's Field."

World War II began in Europe when Clason Kyle was only ten years old. Although the war would greatly impact everyone in the country, Mr. Kyle recalls that he still felt safe in his neighborhood and that his parents never worried about his whereabouts. Oftentimes he would go to one of his aunt's homes. His family afforded him a safe haven, and they enjoyed life in Columbus. One of their favorite outings was to Spano's Restaurant, a landmark in Columbus, where Mr. Kyle liked to dine on scalloped oysters!

Mr. Kyle remembered being at the Bradley Theatre on Broadway when the management stopped the show. It was a Sunday afternoon, December 7, 1941, and the manger announced that Pearl Harbor in the Hawaiian Islands had been attacked by the Japanese. Mr. Kyle said that the moment was a very emotional one, with the moviegoers standing and singing our National Anthem, The Star Spangled Banner, as members of the armed forces, who had been in the audience that afternoon, exited the building. This, the announcement of the bombing of Pearl Harbor, remains one of Mr. Kyle’s most startling and moving memories of the war years. Even as a child, he knew that this meant that the United States would declare war. From 1939 until 1941, we had been involved in supporting the Allies; now we would be one of them. At twelve years of age, Mr. Kyle knew that this was a very serious time.

The Kyle family was in the textile industry (Swift Manufacturing on 6th Avenue is pictured above). It was wartime; toweling and sheeting that was manufactured in the textile mills went to support the needs of the armed forces. The Kyle family supported overall efforts to win the war and, like Americans across the country, the family participated in those activities that benefited the defense efforts. The Kyle family often invited soldiers who were stationed at nearby Fort Benning to have dinner with them at their home.

Like many other Columbusites, they enjoyed the presence of celebrities who came through town on campaigns to sell war bonds. Often times these celebrities were film stars. The Kyle family also collected tinfoil that would be gathered into a ball, then melted and used in the war efforts. "Bundles for Britain" were sent to our allies and Mr. Kyle remembers ladies in Columbus knitting bundles of wool items that were mailed overseas.

Rationing was an ever present circumstance during the war years, and Mr. Kyle recalled that sugar was rationed, and people made their own butter. Tires were retreaded when needed and nylon hosiery was scarce. Where transportation was involved, most people walked, rode bicycles, or took the bus. Today we can be in Atlanta within two hours, traveling via the Interstate Highways. During World War II, however, trips to Atlanta were rare. It was a journey of several hours, as Mr. Kyle recalled traveling through Fayetteville to finally arrive in Atlanta.

The war touched many families, and the Kyle's were no exception. Mr. Kyle's brother was ten years older, and while he was serving in the war, he was wounded in the leg. The family was worried about his safety, and they were relieved when the young man returned home safely.

Soldiers were everywhere in Columbus, and they could often be seen on the streets. The Kyle family felt both sympathy and gratitude toward the young people serving in the armed forces of Mr. Kyle recalled that one of his uncles was a warden who worked with the blackout drills. These drills required special blackout curtains that would make a house as dark as possible. When the signal sounded, the curtains were drawn and everyone stayed inside. Because of his uncle's involvement, Mr. Kyle said that his family members were careful to carry out the drills correctly.

Even during the war years, there were times when entertainment flourished. Children, as well as adults, attended the movies, went to concerts, enjoyed shopping and went about their daily lives. Some local persons found Phenix City, Alabama, just across the Chattahoochee River from Columbus, an enticing destination. Mr. Kyle described Phenix City as "wide open." Although some of its citizens were already making valiant efforts to restore order to their community, it would be years before this would be accomplished. In the meantime, soldiers and civilians alike would go to Phenix City. Vice was commonplace, and Columbus parents warned their children not to go there! Today, Phenix City is a progressive city, one that has overcome its past and provides a good quality of life for those who live and visit there.

One Sunday afternoon during the war years, Mr. Kyle's grandparents hosted a tea in their antebellum home on Twelfth Street (the Swift Kyle House, pictured above). Today there is no yard, but at that time, a lawn and garden surrounded the house. One of the guests was the famed author Carson McCullers, a native of Columbus; another was General George Patton. That afternoon, in the midst of the party, General Patton stepped to the front porch, and there he shot his famous pearl handled revolvers. Mr. Kyle remembered that a "sea of khaki" filled the yard, as soldiers from all around the area poured onto the lawn! It seemed as though two thousand troops were standing in front of the house! As Mr. Kyle expressed it, this is one of his "splendid memories." He also recalled that while most of the guests were dressed in their afternoon best, Mrs. McCullers (pictured below) was dressed in a casual skirt with knee socks and brogans, a style of walking shoe. All in all, it was a very memorable afternoon!

As the end of the war approached, Americans, including the Kyle family, would suffer a loss. President Franklin D. Roosevelt passed away at The Little White House at Warm Springs, Georgia, only a short distance from Columbus. In fact, numerous Columbusites had the opportunity to meet the President when he visited the area, where he received treatment for polio. On that April afternoon in 1945 when Mr. Kyle heard that the Commander-in-Chief had died, he was in his grandfather's optical shop. That day, and in the days that followed, many Americans mourned the passing of the President, the leader of the Free World. People in the street wept with grief.

Later that year, President Harry Truman ordered the atomic bomb dropped on Japan. Mr. Kyle, now a teenager, thought that it was the right thing to do. Like many Americans, he believed that it was the most expedient way to end the war. Looking back, he now says that it was "horrible thing to do, necessary, but morally questionable." Although he acknowledges that President Truman made a decision that must have been difficult beyond our understanding, Mr. Kyle's feelings remain mixed on the issue.

The end of the war brought great joy and excitement to Columbus and to the rest of the country. There were celebrations throughout the city. Downtown Columbus was filled with revelry and the celebrations lasted for hours, throughout the night! Young and old alike joined in the fun! 1945 saw the defeat of Germany and Japan, and the American military came home to a welcoming that has never been equaled!

Clason Kyle grew up and became a newspaperman, a journalist who grew to love the notion of historic preservation. He has long been a spokesperson for the efforts to preserve the historic buildings and neighborhoods of Columbus. As he was also a patron of the arts, the community greatly benefited from his interest. Along the way, Mr. Kyle wrote a book, Images, that reflects the importance and the beauty of Columbus. It remains an important record of life in the city along the Chattahoochee.

For a number of years, Mr. Kyle also worked on a book that told the story of the fabled State Theatre of Georgia, the Springer Opera House. In the spring of 2006, In Order of Appearance was published to acclaim. Once again, Clason Kyle's ability to recollect the times of his life, and to place them into historical perspective, has added to the lore and legend of his hometown, Columbus, Georgia.

Oscar Stanback – interviewed by Forrest Parker, Crytal Nguyen, and Anton Graphenreed

Oscar Stanback was born in Columbus, Georgia, on May 18, 1924. In 1941, he was 17 years old and lived with his parents at 1724 8th Avenue (located on the current site of the Medical Center, now Piedmont Midtown). His mother was a domestic worker, and his father was a common laborer. He had attended Claflin School (pictured above) through the seventh grade and was attending Spencer High School when the war broke out. His mother, wishing for him to complete high school, was able to obtain for him a deferment from the draft. Upon graduation in May 1943, he received his draft notice and reported to Fort Benning for training 10 days later.

He remembers that he did not learn of the bombing of Pearl Harbor on Sunday, December 7th. Few Black families owned radios at that time. He and many of his friends heard about the bombing when they arrived at school on Monday. As a three sport athlete (baseball, football, and basketball), he became a member of the Spencer High School Victory Corps, whose members encouraged other students to buy victory stamps and war bonds. As a member of St. John’s AME Church (pictured below), he also recalls that the church invited African American soldiers to attend services on Sunday, and that church members would regularly take soldiers home on the weekend for a home-cooked meal.

Rationing was a problem for everyone, but since his aunt was a cook for the City Hospital, she would bring home leftovers after work. Gasoline rationing was not a problem since the family did not own a car. Public bus transportation cost five cents per ride, and usually his mother would give him ten cents a day to get him to school and back. However, many times he would walk to school and back (from 18th Street where his house was to 8th Street where Spencer was located) and use the money to buy a snack after school.

For entertainment, he remembers playing baseball at South Commons. One could skate from his house down to Golden Park, choosing routes carefully because some of the streets weren't paved. It was downhill all the way, but the trip home was not as easy.

The YMCA for African Americans was located on 9th Street and 6th Avenue, and this was also a popular hangout for the athletes. Around the corner was the Black USO Club, where dances were held for the soldiers, but rules barred local teens from entry. He recalls that A.J. McClung ran the USO Club. The University of Georgia and Auburn University used to play their annual football game at Memorial Stadium in Columbus, and he and his friends would go down to the stadium to get a peek at the game from the earthen embankments around the stadium. The Liberty Theater showed movies for five to ten cents, and most kids used tokens to get inside.

Mr. Stanback mentioned the subject of "privies," outdoor toilets frequently seen in Columbus even in the 1940's. By this time, privies were not holes dug in the ground as in former times, necessitating frequent filling and moving. Containers were provided by the city and emptied regularly as a city service. Nevertheless, this observation gives an insight into a rarely mentioned area during this era city sanitation.

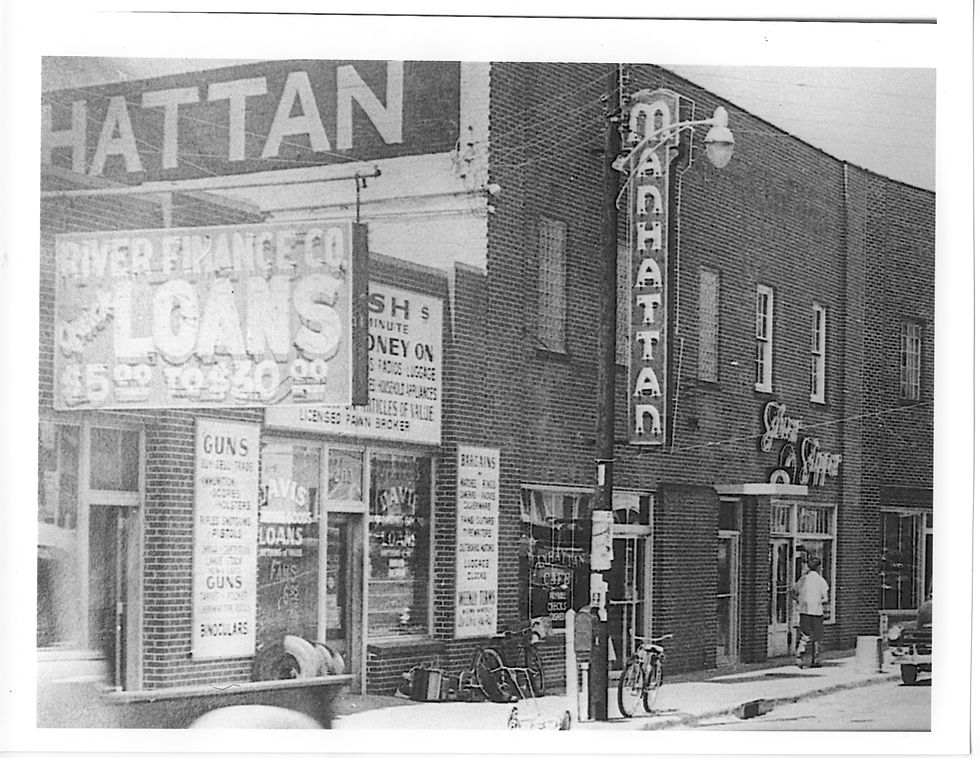

Growing up, Mr. Stanback worked at many jobs to help make ends meet for the family. He noted with pride that he was able in most cases to handle his own needs with the money he earned. He worked at the clothing store Schwobilt as a presser on some weekends, he shined shoes at a local barber shop for five cents a pair. He also worked at V.V. Vick's Jewelry Store in downtown Columbus.

In high school, his football coach, Mr. John Martin, was head waiter at the Bama Club in Phenix City. He would take the senior athletes who had good grades to work weekends at the club. It was hard work, starting at around 5 or 6 o'clock in the evening and working until 3 or 4 o'clock the next morning. Things got pretty rough at times, especially when the paratroopers came in. Mr. Stanback commented, "It was rough, they couldn't keep bouncers." Then he added with a grin, "The paratroopers were the bouncers." However, his aunt put a stop to his working at the Bama Club after she learned how "rough" things were.

After graduating from high school in May 1943, college was "out of the question," and joining the military was a "way out." In June 1943, Mr. Stanback was in the Army and stationed at Fort Benning, playing ball for Special Services, who had found out about his athletic exploits in Columbus.

When not involved in athletics, Mr. Stanback worked as a mail clerk, and also with the Special Training Unit, teaching illiterate trainees enough writing skills to sign their names on the payroll sheet. Although his family lived in Columbus, he lived in barracks on post, since only married soldiers were allowed to live off-post. When "limited service" soldiers (wounded soldiers able to perform light duty) began returning from combat areas, they took over these duties, and Mr. Stanback was assigned to Fort Indiantown Gap for six months to be trained before deploying to the Pacific Theater.

He arrived in Okinawa as the battle for the island was raging, and his unit stayed busy unloading ammunition and equipment off ships until the end of the war. Air raids were common, usually striking the U.S. Forces in the evening around 6:30 to 7:00 pm in the evenings. When the Japanese surrender was announced, he and his buddies "rejoiced" when they heard the news.

Mustered out of the Army in April 1946, Mr. Stanback wanted to continue his education but didn't know where. Morris Brown had offered a baseball scholarship, but his parents thought that life in Atlanta might be a "little too fast," so he decided on Tuskegee Institute. He met his future wife there, getting married in 1946. In 1950, with a Physical Education degree, he was the first Black physical education teacher hired in the Muscogee County School District. After teaching and coaching, he steadily moved up the administrative ladder in the district serving as an assistant principal and then principal before retiring in 1980.

Thank you for joining us this month and reading these wonderful stories! We will be back in August with more Columbus history!

Wakad Wagholi Viman Nagar Vishrantwadi Shivajinagar SB Road Ravet Pune best city Pimple Saudagar Pirangut Marunji Nigdi Pashan Pimpri Chinchwad Magarpatta Lohegaon Koregaon Park Kalyani Nagar Kharadi Pune city Service Pune Star Hotel Hinjewadi Pune desire Pune Airport city Akurdi Aundh Balewadi Baner Bavdhan Bhumkar Chowk Pune city Chakan Dehu Road Deccan Gymkhana Dhanori best city

Visibility is key for any emerging musician. By utilizing Guarantees Radio Interviews & Radio Airplay artists can accelerate fan growth effectively. Airplay ensures your songs are repeatedly heard, while interviews offer a chance to convey personality and artistry. Together, these opportunities increase trust and engagement, helping fans connect beyond just the music. A consistent radio presence builds a professional image, encourages social media growth, and opens doors for live shows or collaborations. For artists ready to expand their reach, radio exposure is an invaluable tool, turning potential listeners into dedicated supporters and accelerating career momentum.

design-build firm

architecture and construction industry

comprehensive design-build solutions

team of architects and engineers

residential and commercial projects

sustainable practices

In today’s competitive world, mastering influence is more valuable than ever. The secret language of influence in the workplace goes beyond words—it involves body language, timing, and emotional intelligence. Subtle cues such as maintaining eye contact, active listening, and mirroring behavior can build trust and authority without direct persuasion. Just as a London mentalist reads hidden signals to understand people’s thoughts, professionals can harness these techniques to foster collaboration, resolve conflicts, and inspire teams. Influence is not manipulation; it’s about creating genuine connections. By practicing these subtle strategies, anyone can become a trusted leader in their organization.

thesis writing service

thesis writing services

academic writing services

dissertation writing service

dissertation writing service

dissertation writing services

custom dissertation writing service

dissertation help

write my dissertation for me

best dissertation writing services

custom dissertation writing service

cheap dissertation writing service