Fort Benning (1953): The Infantry School - 46 Years of Service

- Historic Columbus

- Jul 20, 2022

- 8 min read

Hello everyone! Today is our third installment for the month as we celebrate the history of Fort Benning. The Infantry School can trace its beginnings to the Continental Army in the Revolutionary War. Sources: The Infantry School: 46 Years of Service by LT. William G. Newbold in The Benning Herald, March 1953. W.C. Woodall, Industrial Index (1953) Fort Benning Section. Many images are taken from Fort Benning, U.S. Army. We are highlighting several of local historian W.C. Woodall's Industrial Indexes over the course of this summer. If you aren't familiar with them, they are a wonderful collection of articles on local happenings, business advertisements, and images of new homes put together each year from 1912 until 1960. There are also issues dedicated to Phenix City and Fort Benning. You can find them in the Genealogy Room of the Columbus Public Library and the CSU Archives.

This History Spotlight is comprised of excerpts taken directly from the article: The Infantry School: 46 Years of Service by LT. William G. Newbold in The Benning Herald, March 1953.

The Infantry School can trace its beginnings to the Continental Army in the Revolutionary War. Famous Prussian drillmaster Baron Von Steuben (pictured above) began by teaching the principles of close-order drill, deployment, and discipline to his small and ragged force. It was Von Steuben who first suggested to General Washington the creation of a drill and demonstration team. Lt. General Arthur MacArthur, Jr. (pictured below), father of the illustrious Douglas, revived the idea for the creation of an Infantry training organization at the time the General was in the command of the Pacific coast. From his idea, the School of Musketry came into being (1907), and although old soldiers of that day didn’t visualize it, that school on the coast of California was the beginning of the edifice that we salute as The Infantry School. And so, it went. Classes were small and studies limited to a few weapons, but the new school progressed. In January 1913, we find our infant prodigy making its first step, a move of location from the Presidio to the more centrally located Fort Sill, Oklahoma.

Trouble came and our newly organized college became a dormant institution. This time, it was brought about by the Mexican Border War. Although she became dormant, her name remained on the War Department’s list of recognized service schools. In July 1917, a letter from the Adjutant General ordered a reorganization and a change of name for our school. She was named The Infantry School of Arms. The next event to affect The Infantry School was World War I. Instead of forgetting about the school, officials decided that here was a war that really required trained and competent leaders, so instead of becoming dormant, as had been the case in past times of adversity, it was decided that she should go into full training activities. With the increase in the school’s activity, it was further decided that the Oklahoma location was not large enough to accommodate the increasing numbers of student officers.

The choice of the site selection board stirred a beehive of activity in a quiet Southern community. Folks in Columbus, Georgia had considered themselves and their city very much out of luck. Among Southern cities seeking Army camps, none had tried harder nor met with less success. It seemed that what is now called the “South’s Most Progressive City” was doomed to get along without an Army installation. Then the verdict of the board was announced. The new location of the school was to be Columbus. If you were around on that eventful day, you will remember the excitement that gripped the city. Old folks, young folks, housewives, grocers, merchants – all were agog over the news. Questions were flying. “Where was the post to be located?” “How many soldiers would man it?” And so on. The answers were soon to be had. East of Columbus in the suburbs, on the Macon Road, the temporary campsite was established, and at first occupied only a few hundred acres. Thus, the beginning of Fort Benning took place. But events were soon to materialize that would make necessary another location.

Columbus had her Army camp, small though it was, and the Army had the beginning of its Infantry School. Initial construction moved along at a slow pace. The first group of personnel arrived from the school at Fort Sill. Then, the War Department announced the consolidation of the Infantry School of Small Arms from Fort Sill, the Small Arms Firing School from Camp Perry, Ohio, and the Machine Gun School from Augusta, Georgia at the new post. General Henry Lewis Benning of the Confederacy was recognized as the outstanding soldier to emerge in this vicinity during that war. A group of civic and military officials decided that it would be fitting to name the new camp in his honor and memory. And so, it became known as Camp Benning. To make it official, but without Washington’s knowledge or consent, the camp commander, Colonel Henry E. Eames, ordered a flag raising ceremony and selected Miss Anna C. Benning, the General’s daughter to raise the first flag. Following the ceremony, Colonel Eames took up the matter of the name with Washington and received unanimous approval. Thus, it became official.

General Henry L. Benning

As most of us did in our early days, Camp Benning went through the “growing pains” stage. And with each new pain, it became more apparent that eventually the camp would have to be enlarged or moved to another location that would afford “stretching room” for its ever-increasing strength. Colonel Eames caused a new board to be formed to look around for a suitable new location. Members of the board had looked over the land that the Bussey Plantation occupied, and reported that this site, nine miles south of Columbus appeared to be an ideal location. Camp officials contacted Mr. Arthur Bussey and his initial reaction was favorable enough to warrant elementary proceedings.

So, Camp Benning grew, and along with it The Infantry School grew. The move from the old to the new site ran smoothly. Buildings appeared almost overnight and plans for the new and bigger ones were on the drawing boards. All through the construction Major Paul Jones acted as the Constructing Quartermaster. Everything was going along in good order until the war in Europe came to an end (in 1918). Then just the opposite thing that had caused the near downfall of the school in past years brought new shadows to Benning. Instead of the beginning of a war, it was the end of a war, with resulting economy measures, that called for the immediate abandonment of the post and an order was received to salvage all buildings and equipment. Put yourself in the shoes of Major Jones when he received the “salvage” order. What would you have done? Here’s what he did. Consulting the dictionary, he came up with this definition: “to save!”

Armed with this interpretation, he issued the order that all buildings would be painted with several coats of first-class paint to “save” them. This action resulted in a tremendous dollar savings to the American taxpayer. Colonel Eames immediately went to Washington and had a meeting with members of the general staff. Plainly enough, as we can see today, he scored another victory and instead of abandoning Benning it was decided to set up a peacetime Infantry School occupying more than 100,000 acres of land and employing some 5,000 personnel. Money was appropriated, boards began their work, and throughout the early part of 1919 the combined work of building the new camp and instructing students continued at a rapid pace. Major General Charles S. Farnsworth assumed command of The Infantry School on June 22, 1919, and in September the order was issued for the complete and final organization of The Infantry School as a permanent institution.

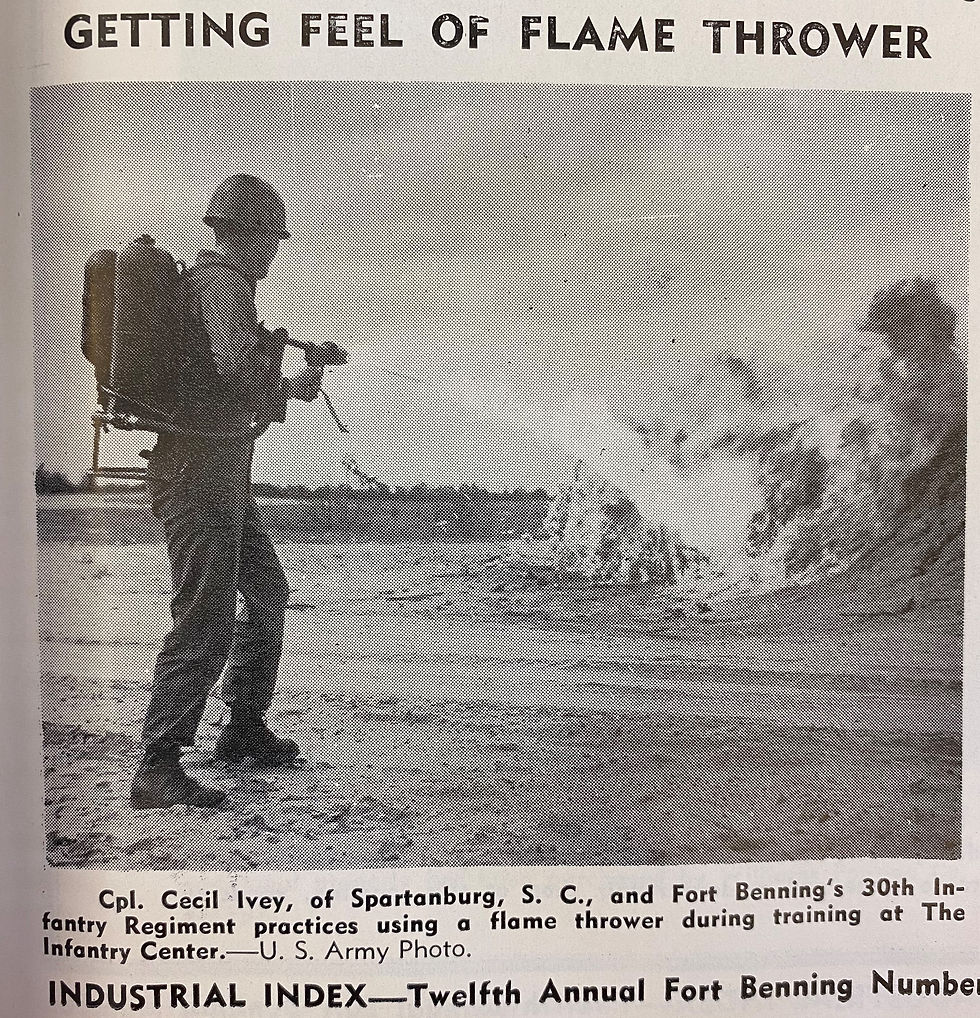

During the period between the two World Wars, The Infantry School continued to give the benefit of its research and developments to the men of the Infantry, not only in tactics and maneuvers to be used in combat, but in allied subjects as well. These included methods of communication, automotive training, the art of cooking and baking, chemical warfare, and staff operations. In addition to the benefits gained from the peacetime period, The Infantry School again proved its worth during the years just before and during World War II when Benning and the school became a virtual beehive of activity. Troops began to pour in almost before the echo of the first bomb at Pearl Harbor had died away. Additional inactive areas became active with the arrival of such distinguished units as the Fourth Infantry Division and the Second “Hell on Wheels” Armored Division under the command of General George Patton.

Regardless of your organization, you pitched in to help train and graduate the more than 100,000 students who went through the many courses offered during the war years. As early as 1939, when the war clouds were gathering over Europe, a mobilization order had included provisions for the training of these students, and the school began full speed ahead operations. What we might term the “third phase” of extended operations began with the arrival of the Third Infantry Division in January 1939. Headed by Major General P.W. Clarkson, the mission of the “Rock of the Marne” was not only to train men to take their places in America’s striking force, but also to serve The Infantry School as demonstration troops. In September 1944, the school graduated and commissioned her 50,000th officer candidate. This milestone was celebrated with a ceremony presided over by Lt. General Ben Lear, then commander of the Army Ground Forces. This climaxed almost three years of war activities during which more than 100,000 students had graduated from the school, not including a like number of airborne students.

The thing that had been our hopes since that December 1941 finally came true in August 1944. First the Germans surrendered, then the downfall of the Japanese empire came about. If you were assigned to the school in those post-war years, it might have looked to you something on the order of a United Nations gathering. Visitors and students from nearly every country came to look at the school. Numbered among these were the great war leaders of the nations who had learned to admire the American Infantryman and the way he acted as a fighting man, or diplomat. They also came to see the techniques that enabled this country to produce such outstanding officers and non-coms in so short a time. The Infantry School and Fort Benning were quietly active again. Peace was still our prayer. But our prayers went unanswered and with the outbreak of hostilities in Korea, coupled with the committing of our Infantry to help stave off the Communist threat, The Infantry School once again took on the old familiar buzz and whirl of a war-time camp.

Today (1953), as their school, under the guidance of Major General Guy S. Meloy, Jr., continues to produce Infantry leaders, these past grads of the courses are returning to their homes. Those who are continuing in the Army are usually assigned to The Infantry School. Here they serve on various teams and committees, passing on to new students the important points of their hard-won knowledge gained on Korea’s fighting front. New students, whose names may someday be ranked with those of Dwight Eisenhower, Omar Bradley, Mark Clark, Lawton Collins, Matthew Ridgway, James Van Fleet, John R. Hodge, William Dean, and YOU, and all the graduates of The Infantry School agree to a man that “There could be no better or truer motto for The Infantry School than the one emblazoned on their blue shield – FOLLOW ME.” For when the chips are down, it is always the Infantry who lead the way! Next Week: Next Thursday, we will have the last installment of Fort Benning history. Thank you all again for your continued interest in these emails and for your support of preservation! See you next week!

In today’s competitive market, customer support plays a critical role in the success of any business. Providing clear communication channels, such as an accessible edreams contact number ensures customers can quickly address their concerns or inquiries. Businesses that prioritize responsiveness build trust and loyalty among their clientele. This strategy not only enhances customer satisfaction but also drives repeat business and positive word-of-mouth. Ultimately, establishing strong support systems reflects a company's commitment to excellence and sets it apart from competitors in a crowded marketplace.