Nunnally Johnson: A Columbus Man in Hollywood

- Historic Columbus

- Sep 21, 2022

- 8 min read

Hello everyone! Today, we are celebrating the life and work of screenwriter, producer, and director Nunnally Johnson. By the 1950s, he was the highest paid screenwriter in Hollywood. Nunnally had a prolific career, and it has been a pleasure to learn more about his work. I've also included, at the end, a few excerpts from his daughter's 2004 novel about her life during the height of her father's career to shine more light on his life in Hollywood. SOURCES: Lloyd, Craig. "Nunnally Johnson." New Georgia Encyclopedia, last modified Aug 2, 2018. Nora Johnson, writer who created ‘The World of Henry Orient,’ dies at 84 BY STEVE MARBLE, Los Angeles Times, OCT. 11, 2017. “Nunnally Johnson, Screenwriter, Producer and Director, Is Dead.” By Peter B. Flint, The New York Times, March 26, 1977. Coast to Coast by Nora Johnson, 2004. “A collection of his correspondence Nunnally Johnson, Screenwriter, Director, Dies” By Juan Williams March 27, 1977.

Nunnally Hunter Johnson was born on December 5, 1897, in Columbus to Johnnie Pearl Patrick and James Nunnally Johnson. His father worked as a superintendent for the Central of Georgia Railway, and his mother was an activist on the local school board. An avid reader with an acute sense of humor, Johnson grew up and attended school in Columbus, his mother’s hometown. In later life he remembered fondly his youthful days delivering on his bicycle the Columbus Enquirer-Sun, attending theatrical productions at the Springer Opera House, and playing first base on the Columbus High School baseball team. Johnson later recalled the YMCA building, the marble structure on 11th Street and built in 1903 with funds donated by George Foster Peabody, as his “social club.” After graduating from Columbus High in 1915, Johnson worked briefly as a reporter for the Columbus Enquirer-Sun before moving to Savannah to work for the Savannah Press. He continued to visit Columbus annually until his father’s death in 1953.

Nunnally Johnson's parents purchased 1136 Dinglewood Drive in 1934. Nunnally's mother, Johnnie Pearl Johnson, founded the first parent-teacher association in Columbus and was the originator of the PTA Council in 1905. She was also a strong advocate for teacher welfare and for the education of African American children in our community. Johnson Elementary is named after her.

In a 1969 oral history, Nunnally said the following about his early days. “Well, I guess one of the truest things I ever heard, which would apply to my childhood, was what Dwight Eisenhower said. He said, "I suppose we were poor, but we didn't know it." You know it's a very true thing. My father didn't make much money. In this small town, there was nobody in my family that had ever had anything to do with writing. My father was a coppersmith, at the railroad, Central of Georgia. I can't think of how I ever got around to the idea of writing, except that I wanted to be a newspaperman. I think that must have come up. That seemed to be within the possibilities of my life. But I wanted to be a newspaperman because I saw a picture of Richard Harding Davis in his war correspondent's outfit, and that looked to me like the kind of life I'd like to lead. A lot of kids are influenced by what they read.” Nunnally Johnson joined the Georgia Hussars, a cavalry unit, and went off to the Mexican border war. He remained in the Army throughout World War I. In 1919, Johnson moved to New York City and by the mid-1920s had emerged as one of the city’s leading newspapermen, reporting major national events for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle (1919-25), the New York Herald Tribune (1926), and the New York Evening Post (1927-30). At the Evening Post, he also penned a weekly column of humorous social commentary under the heading “Roving Reporter.” From 1925 to 1932, he published fifty short stories in the Saturday Evening Post and several stories in the New Yorker. These writings were mostly light satirical pieces depicting contemporary manners and mores in New York City and in a fictionalized version of Columbus that he called Riverside. Three of his stories won O. Henry Memorial Awards in the late 1920s. In 1931, he published a collection of his stories, There Ought to Be a Law.

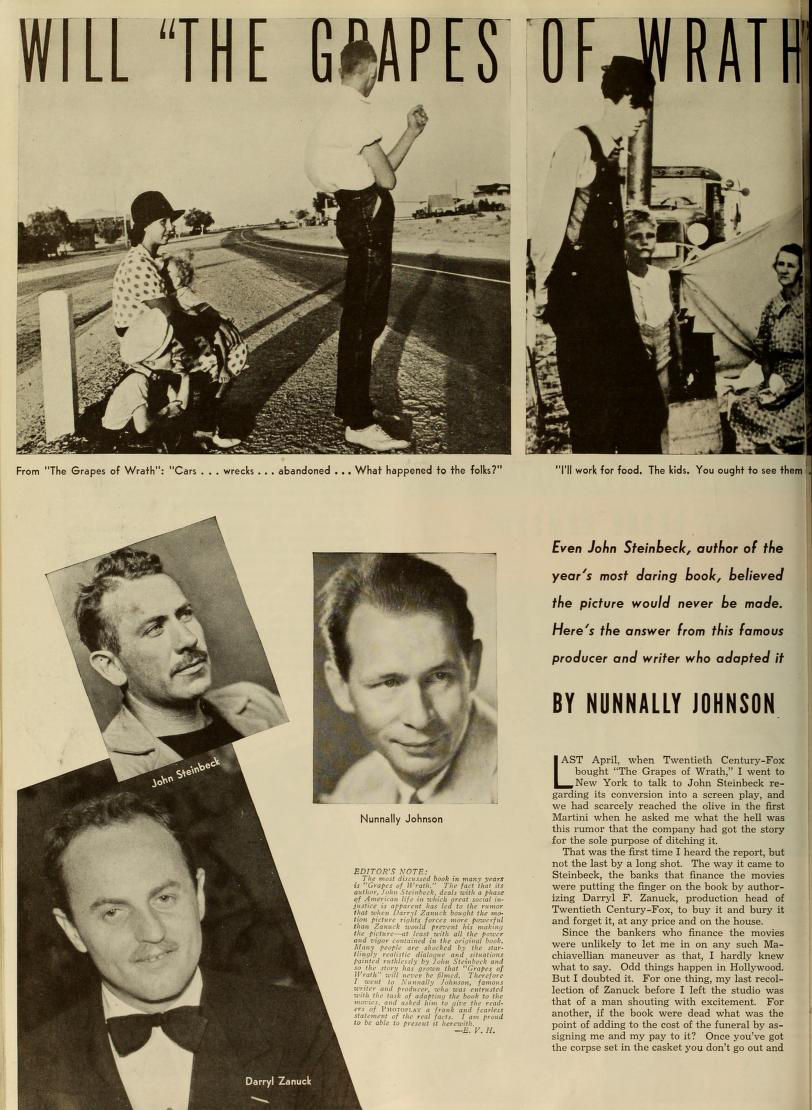

In 1932, Johnson moved to Los Angeles where he worked as a screenwriter for Twentieth Century Fox. Among the dozens of scripts he wrote, he excelled at converting novels into screenplays. His most successful efforts included screenplays for John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath (1940) and The Moon Is Down (1943); The Keys of the Kingdom (1944) and The Man in the Grey Flannel Suit (1956), both of which starred Gregory Peck; Daphne du Maurier’s My Cousin Rachel (1952); and his final screenplay, The Dirty Dozen (1967).

Steinbeck didn't think Grapes of Wrath could be filmed. After one of his trademark marathon writing sessions on July 5, 1938, a day when he wrote 2,200 words, an entire chapter at a single sitting, Steinbeck wrote to his agent: "I am quite sure no picture company would want this new book whole and it is not for sale any other way. It pulls no punches at all and may get us all into trouble but if so -- so." Darryl F. Zanuck, head of production at Twentieth Century-Fox, was the closest thing to a political liberal the industry could offer in its front offices. In The Grapes of Wrath, Zanuck, an exceptionally able "story man," also saw a dramatic tale of human courage, already loaded with expressly cinematic episodes. Zanuck, during his days in a similar position at Warner Brothers earlier in the decade, had made that studio the home of punchy, breathless films about the Depression, like Wild Boys of the Road and Heroes for Sale. He envisioned The Grapes of Wrath as two kinds of film at the same time. First, it would be a document about the men and women whom Franklin Roosevelt had called in early 1933 "ill housed, ill-fed, and ill-clothed... the pall of family disaster hanging over them day by day." Second, it would be a drama of fundamentally American optimism, of the triumph of "the little people" over the tyranny of economics and the poison of class prejudice. Director John Ford assembled a team of creative people for the film without equal. Screenwriter Nunnally Johnson and leading man Henry Fonda turned in arguably the most memorable work in their long careers. In 2006, the Writers Guilds of America, east and west, named Johnson’s adaptation of The Grapes of Wrath on their list of the 101 greatest screenplays.

Nunnally worked in other genres as well. Among his most popular productions were the musical Rose of Washington Square (1939) and the comedy How to Marry a Millionaire (1953), one of actress Marilyn Monroe’s earliest films. In 1943, Johnson left Twentieth Century-Fox to John William Goetz and Leo Spitz in forming International Pictures which in 1946 was merged with Universal Pictures to make Universal-International. By the 1950s, Nunnally Johnson was the highest-paid screenwriter in Hollywood. Two of Johnson’s most important adaptations were Georgia-based stories: Erskine Caldwell’s Tobacco Road (1941), his third partnership with the director John Ford, and The Three Faces of Eve (1957), based on a true case of a Georgia woman with multiple personality disorder. That film, which Johnson also produced and directed, earned an Academy Award for actress Joanne Woodward, a Thomasville native, in her first starring role.

Nunnally Johnson with Joanne Woodward and her husband Paul Newman

Johnson's first marriage in 1919 at Trinity Church in Brooklyn Heights was to Alice Love Mason, with whom he had one daughter, film editor Marjorie Fowler. Mason was an editor with the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Mason and Johnson divorced in 1920. His second marriage was to Marion Byrnes in 1927, also a staff member of the Daily Eagle, with whom he also had a daughter, Nora Johnson. Byrnes's and Johnson's marriage ended in 1938. While filming The Grapes of Wrath, Johnson met his third wife, actress Dorris Bowdon, a Mississippi native. The two were married at the home of Charles MacArthur and Helen Hayes in Nyack-on-the-Hudson on February 4, 1940. They had three children and resided in Beverly Hills.

Nora Johnson with her father

Nora Johnson was born in Hollywood on January 31, 1933, when her father was already well on his way to a prominent career. Her mother, Marion Byrnes (Nunnally’s second wife), left her father when Nora was a young child, taking her to New York. In her book Coast to Coast she talks about her family and her father. “I was born in the old Hollywood Hospital a few years after the talkies came in. You might even say because the talkies came in, since the reason we were there was so my father, Nunnally Johnson -- along with hundreds of other writers -- could make money writing dialogue for the movies. It was the depths of the Great Depression, the bottom of the birthrate curve, the year Franklin D. Roosevelt took office, the end of Prohibition, the year we went off the gold standard, the day after Hitler came to power...but Los Angeles was a boomtown. The local news was Cavalcade won the Oscar for Best Picture of 1933, and Nathanael West sold Miss Lonelyhearts to Zanuck for his new Twentieth Century Pictures. It was the year the Screen Writers Guild was founded, the year of drought and the Dust Bowl and the earthquake that cost $40 million and killed 120.

My father's first salary, $300 a week, doubled in a year, and went to $2,000 five years and twenty scripts later. Much happened during that time. We moved from Bedford Drive to Maple to Beverly to Camden. Hedy Lamarr's picture Ecstasy was seized by the U.S. Customs for indecency. Nunnally produced Dimples, starring Shirley Temple. Bertolt Brecht, Arnold Schoenberg, and other future Hollywood artists fled the darkening political scene in Europe. My father turned down a certain Civil War novel because he thought nobody would go and see a picture about two people named Scarlett and Rhett.

While his star rose, my mother went to auctions, decorated houses, played polo, and took speech lessons to get the Flushing (Queens) out of her voice. While he talked, laughed, and drank at the Brown Derby and Chasen's with the likes of George Jessel, Ben Hecht, William Faulkner, Herman Mankiewicz, Philip Wylie, Gene Fowler, Harry Ruby, Oscar Hammerstein, Dorothy Parker, Ogden Nash, Jack Benny, George Burns, Groucho Marx, Robert Benchley, Don Stewart, and Dash Hammett, she lunched and played badminton, had facials and massages, and, at one party, held the inebriated Scott Fitzgerald's head in her lap. In 1938 the rains came, ending the drought. Dorris Bowdon came to Nunnally's office, determined to get a part in Jesse James. My mother, the nanny, the Swedish chauffeur, and I packed up the big black Cadillac and drove to New York, leaving California forever. The next year The Grapes of Wrath opened with Dorris Bowdon playing Rosasharn, and in February of 1940 Nunnally and Dorris' marriage was announced on the radio by Walter Winchell. After their divorce my parents sent me back and forth twice a year. I was supported by the gold on one coast and schooled on the other. We learned how to have two homes, to drop names of stars and producers and restaurants, to be two people at once."

Nunnally Johnson is one of the most respected and admired screenwriters in the American film industry, because of his skill and craftmanship. He consistently wrote good scripts for over thirty years and was involved with some of the most successful (both artistically and financially) films to have come out of the American film industry. Curiously enough, Johnson never won the highest honor of the industry, the Academy Award, which puts him in the same category with such other "losers" as Gary Grant, Greta Garbo, and Charlie Chaplin. Nunnally Johnson died on March 25, 1977, in Hollywood. Next Week: Next Thursday, we will continue exploring our community's cultural arts history through another Columbus icon - Carson McCullers. Thank you all again for your continued interest in these emails and for your support of preservation! See you next week!

Dolls have enchanted children and collectors for centuries, offering a unique blend of nostalgia and creativity. Modern dolls vary from realistic figures to imaginative fantasy characters, each crafted with care. Checking product details helps buyers understand size, materials, and articulation, ensuring the perfect choice for play or display. Collectors often seek limited editions, while children enjoy interactive features that spark storytelling and role-play. Beyond toys, dolls reflect culture, art, and history, making them more than mere objects—they are companions that carry memories and inspire imagination.

Achieving screen printing success requires attention to detail and the right techniques. Start by preparing your screen properly and using high-quality inks for vibrant results. Consistent pressure and speed during printing ensure sharp designs. Don’t forget to clean your screens thoroughly after each use to prolong their life. For beginners and pros alike, resources like https://allcolorscreen.com offer valuable tools and guides to enhance your skills. Following these tips will help you create crisp, durable prints every time, making your screen printing projects truly stand out.

In addition to physical care, many help at home services also offer cognitive stimulation programs. These www.helpfulhandsinhomecare.com programs engage individuals in memory exercises and other activities that help keep the mind sharp. This is especially beneficial for elderly clients who are at risk for cognitive decline or memory loss.

The iSQI CTFL_Syll_4.0 Certification Exam is designed to validate your expertise in software testing principles and practices. Covering a wide range of topics, this exam equips you with the skills needed for quality assurance roles in software development. By earning this certification, you demonstrate your understanding of test processes, techniques, and tools, boosting your credibility in the industry. Prepare for success with the iSQI CTFL_Syll_4.0 Certs Exam and enhance your career prospects in software testing and quality management.