The Old Beloved Path (Part 5): The Mississippian Period

- Historic Columbus

- Dec 7, 2022

- 9 min read

SOURCE: The Old Beloved Path: Daily Life Among the Indians of the Chattahoochee River Valley, William W. Winn, 1992. Cover art by Joe Belt. Illustrations by Cheryl Mann Hardin with plant drawings by Faith Birkhead. Sponsored by the Historic Chattahoochee Commission and The Columbus Museum in cooperation with the Chattahoochee Indian Heritage Association.

The Mississippian Period, so named because of the tremendous mound complexes from this period found in the Mississippi River Valley, was a time of intense social and religious activity, full of pomp and ceremony, and, if anything, of even more elaborate ritual than the preceding Woodland Period. The Spanish explorers of the 16th century encountered evidence of this once-great Indian civilization throughout North Florida, Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee, and the Carolinas. In fact, some of the ceremonial mound centers functioned until the early 17th century, although the vast majority appear to have gone into sharp decline much sooner. Initially, archeologists attributed this decline to conquest by an invading group of Native Americans, supposedly, in our area, the historic Muskogulgi or Creeks. However, new evidence suggests that epidemics of European and African diseases, introduced by contact diffusion from the Caribbean following Columbus’ initial voyage in 1492, may have decimated the Mississippian people in the Southeast, including those who once inhabited the Chattahoochee River Valley. Fortunately, archeological record from the period is extensive in the Chattahoochee River Valley. From these remains, and from accounts of early Spanish and French explorers, who first came into contact with the Mississippian people in the 16th century, we can reconstruct a much more detailed picture of daily life in the Valley than has been possible for any previous period.

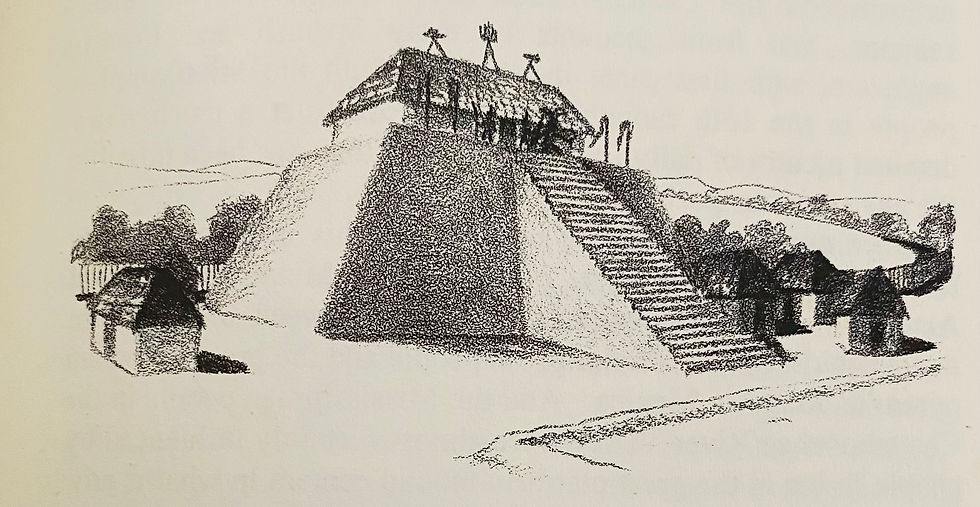

Once again, the ultimate impetus for this culture seems to have come from the west, perhaps from Mexico or Central America. There are distinct similarities between the platform mounds built by the Mississippian people and the pre-Columbian pyramids found in Mexico. And the Mississippian people in the Chattahoochee River Valley were almost certainly influenced by people living at the great platform mound centers in what is now the central United States, including those near Cahokia, Illinois, and Spiro, Oklahoma, and more immediately, at Etowah (pictured above) in North Georgia, the Macon Plateau in Central Georgia, and Moundville, Alabama. Some authorities think the Mississippian sites on the Chattahoochee were established by people radiating outward from what is now Alabama, perhaps as emigrants from a powerful chiefdom. This movement might explain the moats and palisades protecting many Mississippian sites in the Valley, necessary defenses against a displaced indigenous population. Other authorities believe Mississippian culture, including its religious beliefs and paradigms for social organization, was primarily spread through a process of contact diffusion. One way this could have happened is through the widespread trade network that may have linked the civilizations of Mesoamerica with the Mississippi River Valley mound centers, including those in Ohio and Illinois, and that most certainly linked the latter with mound centers on the Chattahoochee and elsewhere in the Southeast. It has even been suggested that a group of traders, known to the Aztecs as pochteca, may have been frequent visitors among the native people of the American Midwest. Some of the traders may have settled there, bringing with them foreign notions of social ranking, religion, and even human sacrifice. In turn, these new ideas reached the Chattahoochee via the old trade routes that had connected the Valley people with the Midwest populations since at least early Woodland times.

Mississippian Settlements Mississippian villages were usually situated on large rivers or streams. They appear to have been placed so as to make them adjacent to ich bottomlands, for farming, and accessible to diverse ecosystems – uplands, coast plain, Gulf coast – which allowed for maximum exploitation of natural resources. The sites are marked by huge, rectangular, flat-topped platform or temple mounds which served as bases for religious reliquaries, charnel houses, elite residences, or council houses. Often these platform mounds were arrayed around open plazas. Extensive village areas surrounded the plazas. Sometimes the entire site was surrounded by a moat or palisade, an indication that ither the settlements were made in hostile territory or that they were threatened by other groups in the area. Platform mound building is only one of the traits that distinguishes Mississippian culture. The appearance of extensive river bottom agriculture is another feature which sets the Mississippian people off from their predecessors. The platform mound builders were not only hunters and gatherers of wild food, but they were also farmers who cultivated seed plants, corn, pumpkins, beans, squash, and probably tobacco in large fields along the banks of the Chattahoochee. By observing where wild plants grew best, and by trial and error, the Indians of the Valley discovered that bottomland soils produced better and bigger crops. Periodic flooding assured regular restoration of nutrients in the soil along the river and its tributaries.

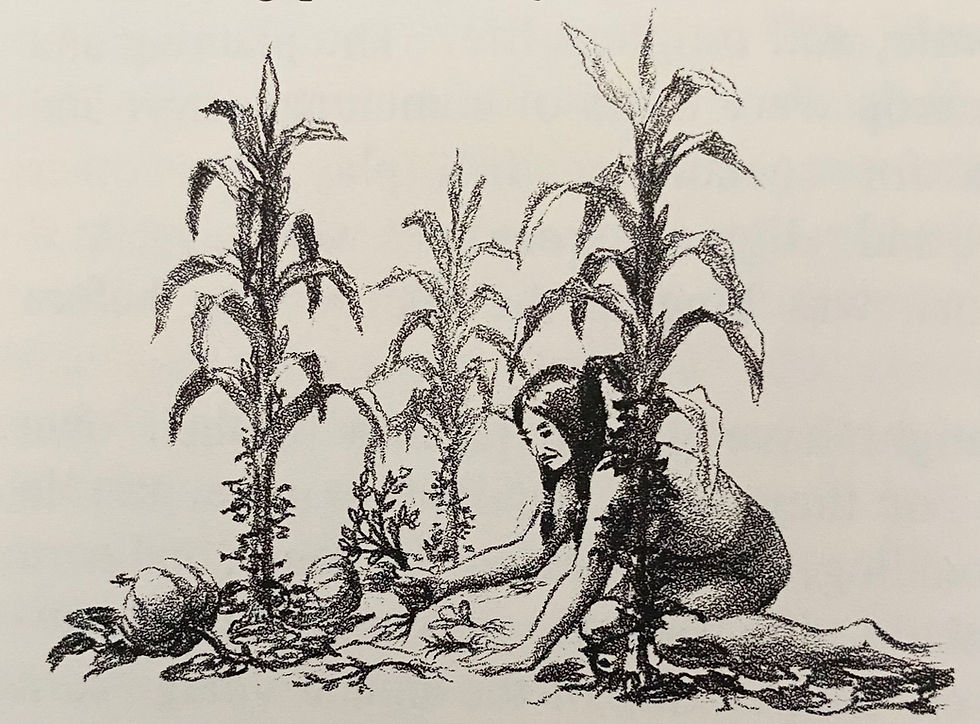

Corn Culture Mississippian people continued to grow and experiment with wild seed plants, just as they had done during the Woodland Period. However, corn – actually a form of maize – was the most important crop grown by the Valley Indians. They became increasingly dependent upon a good crop for survival, so much so that the cultivation, planting, and harvesting of the annual corn crop assumed a primary role in the people’s social, economic, and religious life. The planting and harvesting of the corn crop were times of communal effort and celebrations, occasions for socializing, ball play, and other games. Important civic and religious ceremonies were associated with the harvest. Corn was king in the Valley long before cotton. Ordinary people might have garden patches of their own around their homes, but they were required to take part in cultivating, planting, tending, and harvesting the communal corn fields. In fact, the whole village was involved. Each village seems to have had one person, perhaps a priest or shaman closely associated with the sun god or plant kingdom, who was in charge of the annual corn crop. At the time he thought proper, he would summon the people by blowing on a conch shell or beating on a drum. Then he would lead them in procession to the fields to be planted. The men cleared the land by hand – the horse was not introduced into the Southeast until the Spanish came in the 16th century. Cultivation was done with a hoe often consisting of a wooden pole with the should blade of some large animal affixed to the business end. The women planted. Planting took place in the spring, probably in late April or early May after the frost. Women used long pointed sticks to make shallow holes in the ground. Seeds were dropped into the holes and covered with a few inches of soil. Women, old men, and especially boys watched over these communal fields.

Community Life During the Mississippian Period, community life reached a high point of development. Daily life was perhaps more advanced and more comfortable than at any time before or since for the native people of the Valley. The great platform mounds were surrounded by extensive villages of neat huts constructed of sapling uprights lathes with river cane daubed with clay – the so-called wattle and daub technique – that were great improvements over earlier domiciles made of sticks and animal skins. Farming and maximum exploitation of wild food sources, including storage of surplus corn, nuts, berries and fruits, assured a steady food supply, thus freeing males from some of the tyranny of the hunt and women from constant foraging for wild foods. It would be a mistake, however, to think that life was suddenly easy for the people of the Chattahoochee River Valley, especially by today’s standards, or that all the people shared equally in the benefits of society. Women, in particular, worked very hard.

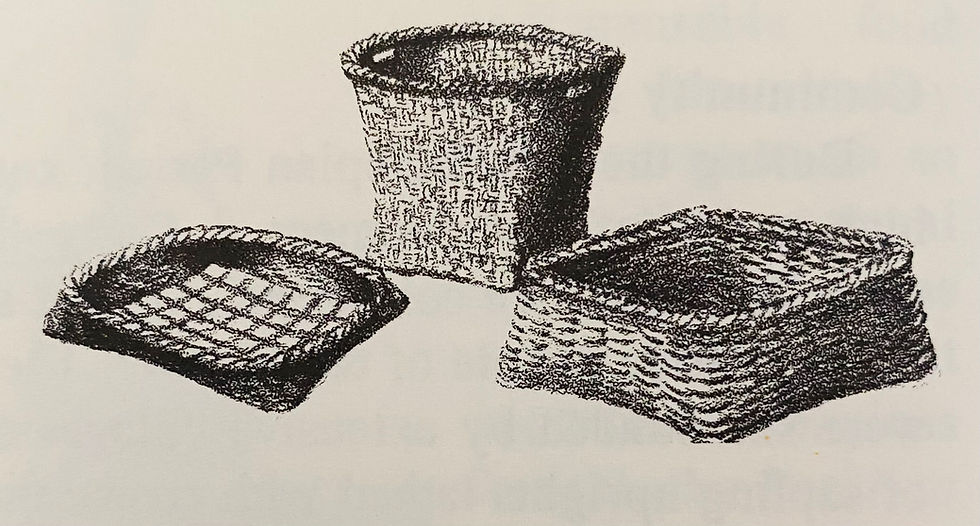

The Work of Women In addition to childbearing and rearing, Indian women were responsible for much of the new agricultural labor, for tending their own family’s garden plot, and for almost all domestic chores and home industry. This latter included cleaning and preparing food, making pots and other cooking utensils, cleaning and curing hides and converting them to clothing, and continuing to collect wild plant foods. Domestic manufacture occupied much of their time. From the inner bark of the mulberry tree and from basswood bark and the bark of the slippery elm women made thread and rope, wove a kind of cloth, and made netting for their own hair. Sometimes they turned Spanish moss into thread and the thread into garments. They made baskets, trays, sifters, sieves, and mats from split river cane and oak or hickory splints, often staining the splints with a black walnut dye. Making and firing pots was another constant task, for the clay vessels shattered with distressing frequency, as the many thousands of potsherds found throughout the Valley today attest. Making cooking pots and other domestic vessels was a more difficult job than might at first appear. Not only did the women have to locate and dig their clay, but they also had to mould and dry the pots and then stand watch as they were fired. Hickory bark seems to have been the preferred fuel for firing because it produced high heat that lasted for a long time. Women also gathered the wood for cooking fires, a job which often required them to journey far from home.

How Buckskin Was Made One of their toughest jobs was the cleaning and preparation of animal hides. Prior to the coming of the White man, almost all hides were converted into clothing or sleeping robes. Some were made into rawhide or fashioned into pouches, bowstrings, and the like. Almost any animal hide could be used in some fashion, but the most sought after were those of the deer, bear, and perhaps buffalo. Of these three, the skin of the white-tailed deer was by far the most important. Women fashioned almost every article of everyday clothing from deer hide, working it and working it until it was as smooth and supple as cloth. The process by which they converted raw deer hide into buckskin differed slightly from individual to individual, but it was always laborious and included the following steps. As soon as possible, the skin was removed from the dead animal. Timing was of the essence. As soon as it was removed, it was placed in a creek or river to soak for four or five days. Following a thorough soaking, the hides were placed across a log or a bent sapling to grain – to remove the hair and the dark epidermis. Almost any instrument with a square edge would do for this part of the processing, provided it was not so sharp it could accidentally cut through the hide. After graining, a sharp flint knife was used to flesh the skin completely. Then the skin was dried in the shade and soaked again overnight. The next morning it was taken out and worked by hand, being twisted and stretched until soft as a cloth. At this point, fresh deer brains were rubbed into the skin to further soften it and help cure the hide. The women repeated this stage of the process over and over until they were satisfied that the skin, which would now be quite white and as soft as chamois cloth, was ready to be smoked. Smoking gave the skin the desired dusky color, helped make it rain-resistant, and increased the likelihood of it drying out soft after being wet. No heat was allowed to reach the hide, just smoke. After this, the skins were set aside to season before being turned into clothing.

Southeastern Ceremonial Complex Some of the most beautiful and interesting artwork from the Mississippian Period is found in the symbols and artifacts associated with the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex. This complex of painted or carved symbols, ceremonial objects, go-animal representations, and costume paraphernalia, which appears at mound centers from the Great Lakes to Florida and is especially well-represented at Spiro, Etowah, and Moundville, was originally called the Southern Cult. Archeologists and anthropologists originally thought the symbols and other elements of the complex indicated existence of a shared system of religious beliefs among the Mississippian people throughout the Southeast. Now, however, students of the subject are more inclined to view the complex in a secular light. Some Southeaster Ceremonial Complex motifs may represent spontaneous expressions of the people’s mythology and folk beliefs. Others appear to relate to fertility, war, and political authority. Still, others may represent plants or be symbols of animal gods, often anthropomorphized, feared, and venerated by Indians throughout the region. Whatever its particular function, the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex is a fascinating element of the daily life of the Mississippian people, including those who lived in the Chattahoochee River Valley. The particular meaning of the iconography may not yet be understood, but it is composed of a clearly recognizable set of symbols, a circumstance that points toward the existence, in Mississippian times, of a widespread, underlying way of looking at the world. Such a comprehensive view of the world as is indicated by the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex hints at a rich mythological life among the Mississippian people, itself indicative of a shared and deeply felt sense of cultural identity. In other words, what we may properly call a civilization existed among native American people of the Southeast, including those in the Chattahoochee River Valley, just prior to the arrival of Europeans in the New World.

Next Week: The last History Spotlight of the year will finish The Old Beloved Path with the customs and daily life of the Indians of the Valley during the period of AD 700 - 1600. Then, we will take a break for the holidays! See you next week and thank you again for your continued love of our community's history.

Comments